One of the hard lessons I’ve learned over my career is that anything worth doing needs to be done several times before you can evaluate it. The Experience Curve as a concept has been with us since 1885, yet many are still unaware of this common sense insight on how people learn and what it means for management decisions.

One of the hard lessons I’ve learned over my career is that anything worth doing needs to be done several times before you can evaluate it. The Experience Curve as a concept has been with us since 1885, yet many are still unaware of this common sense insight on how people learn and what it means for management decisions.

Here are a couple of examples, one from observing schools adopt new curriculum materials and one from my experience as a CEO. Both are relevant to education companies.

New Curriculum Materials

It is common knowledge that it takes 3 years before you can really judge the results of a new textbook/app/activity etc in the classroom. The reason is fairly straightforward and has nothing to do with the students’ learning curve. It has everything to do with the teacher’s experience with the tools. They need to master the new materials themselves and adapt them to their mix of talents.

The problem is that many schools and external observers don’t want to wait that long for results. So they jump to conclusions far too quickly about whether or not something is working. Anyone who is seriously attempting to drive change in the school world should study the experience curve and set their expectations accordingly.

Patience and persistence will pay off for those willing to put the time in. If I’m funding a three year efficacy study I’d much rather look at the teacher’s effectiveness than at the student outcomes (since they rarely have the same students for 3 years).

Corporate Strategy

In business anything worth doing has to be done multiple times before the organization can benefit from it. With small things (e.g. a new payroll process) people seem to intuitively grasp and accept this. “We’re just working the kinks out” & “give us a couple of cycles” are all phrases tossed around to express this idea.

The challenge seems to come at the strategic level. Here, because the risks are so much higher, there seems to be an unrealistic push to get it exactly right the first time.

Take, for example, acquisitions. Many smaller companies approach an acquisition as a one time deal – an attractive target is for sale and they jump on it. The real question that ought to be asked is “are acquisitions a general strategy we are going to employ?” If not, I’d suggest taking a pass on the deal. If you don’t have the resources to do multiple purchases and the stomach to stumble a bit on the first couple you should not go down that path in the first place. No one is magically immune from the Experience Curve (although statistically some will appear to be).

Summary

When you are looking at big strategic decisions factor this in by insisting on answers to the following questions:

- Are we willing to do this many times until we get it right?

- If the answer to “1” is yes, then do we have the money and bandwidth to do it multiple times?

- How are we going to track how we are improving over successive cycles and how can we consciously incorporate what we learn each time?

In both schools and corporations this is a fundamental governance and leadership issue that doesn’t get nearly the respect it should.

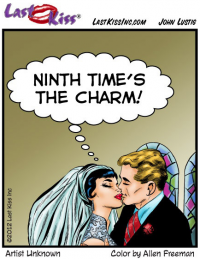

You’d think we’d learn….

The Education Business Blog

The Education Business Blog